Ninety-three percent of attendees support implementation of the Metropolitan Sewer District of Greater Cincinnati's (MSD) Lick Run Alternative over a more costly underground tunnel, according to results from the third public community design workshop held February 23 at Orion Academy in South Fairmount.

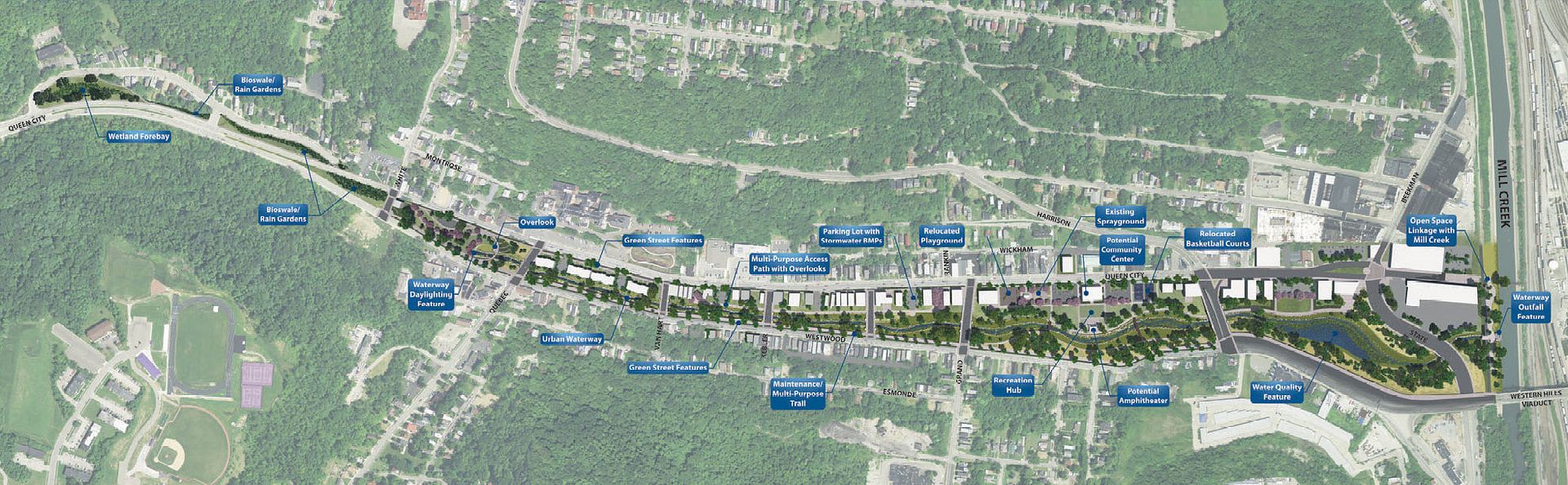

Ninety-eight people – 58 percent of whom either live, work, or own property in the Lick Run watershed – attended the input session to help refine the alternative, which would "daylight" the long-buried creek within a six-block area bounded by White Street, the Western Hills Viaduct, and Queen City and Westwood avenues.

The alternative is a component of the larger Project Groundwork, a $3.2 billion, multi-year initiative to rebuild and improve the region's sewer system.

Project Groundwork is mandated by a 2002 consent decree between MSD and the U.S. Department of Justice, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Ohio EPA, and the Ohio River Valley Water Sanitation Commission that requires MSD to capture, treat, or remove at least 85 percent of the 14 billion gallons of annual combined sewer overflows (CSOs) and the 100 million gallons discharged annually from sanitary only sewers by 2018.

The 2,700-acre Lick Run watershed is home to the largest CSO in Hamilton County, discharging annually a 1.7 billion-gallon mix of raw sewage and stormwater directly into the Mill Creek. Once an open stream, the CSO now runs through a 19.5-foot-diameter pipe that runs approximately two-thirds of a mile underneath the streets of the neighborhood.

The Lick Run Alternative would eliminate about 800 million gallons in annual volume from its CSO.

It also would have half of the capital cost and approximately one-third of the operation and maintenance costs of an underground tunnel, estimated to cost $244 million in 2006 dollars. Additionally, MSD believes that the alternative will aid the neighborhood by creating a viable, walkable business district; enhancing the local transportation network and streetscape; creating a multi-use cultural trail and a civic/recreation hub; and promoting market-driven land development.

Preservation concerns

Attendees identified the lower up-front and lifetime costs, potential for urban revitalization, neighborhood beautification, and ecological benefits as the main strengths of the plan. But many also worried about the impact to existing businesses, traffic and parking issues, the lack of a clear economic benefit and the lack of funding as major weaknesses.

Then, there's the loss of historic building fabric.

Paul Willham, who writes the Victorian Antiquities and Design blog and is president of South Fairmount's Knox Hill Neighborhood Association, believes that the demolitions required to implement the alternative will represent the single largest wholesale urban renewal demolition since the loss of Kenyon Barr in the 1960s to Queensgate and Interstate 75.

"The loss of the South Fairmount business district would be yet another example of the failure of this city, and historic preservation, and further destroy our national image," he wrote on his blog on February 12. "As a preservationist you know we can't save them all, but we can save Fairmount."

Willham wrote that an alternative proposal, which would daylight Lick Run farther west in the basin, should be used instead. He blames the South Fairmount Community Council, whom he says "never saw a building they didn't want to tear down".

"This plan would never be considered in an area like Hyde Park but for some reason its 'OK' in 'poor' South Fairmount," he wrote. "There is nothing 'green' about putting 80 pre-1900 buildings in a landfill at a cost of millions of your local, state and federal tax dollars."

MSD will submit its preferred remedy for resolving CSOs to the U.S. EPA and other regulators in December. If approved, construction of the plan's major elements could be completed by 2018.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

CONTACT AND SUBSCRIBE

CINCINNATI PHOTO GALLERIES

Site Archive

IN THE NEWS

- River cities' trail to get underway

- Streetcar work begins on Main Street between Sixth and Court

- Problems plagued canal projects

- Letter: What happens when bridge is paid off?

- Letter: Expand toll base to move Brent Spence forward

- Cincinnati streetcar reaches (literal) milestone

- New rehab hospital planned for Evanston

- TriHealth to open new hospital in Evanston

- TriHealth to open new hospital

- More lanes closing to make way for streetcar construction

- Letter: Curtail wasteful spending to fund transit projects

- Letter: Transportation choices are lacking in Cincinnati

- Letter: How would Brent Spence tolling bills be enforced?

- And 54 months later ... done?

- Parking the SUV, catching the bus

- Planting a greener Covington

- Report: Pedestrian fatalities fall in Ohio

- Walnut Hills' Five Point Alley event encourages community input

- Need a ride? Uber arrives with two transportation options, Metro adapts bus service to young riders

- Cincinnati Transit Blog: Reactionary Incrementalism

- The River City News: Photos: NKY Restoration Weekend & Take the State Preservation Survey

- The River City News: Editorial: Businesses Believe New Bridge is Critical

- AVB: Is Brent Spence debate a bridge too far?

- Editorial: OK gambling in Kentucky, but do it right

- Arlinghaus: Kentucky is losing money to its neighbors

- Opinion: Gambling preys on the poor

- Zoning code alternative in limbo

- 'A good problem': Construction projects booming in downtown, OTR

- CincyBiz Blog: Could Burnet Woods be Cincinnati's next great public space?

- Catholic Health Partners considering 2 sites for HQ

- Letter: Tax electric cars and bicyclists

- OTR move a boon for CORE Resources

- The River City News: Editorial: Need for Brent Spence Corridor Project Not Going Away

- CincyBiz Blog: Regional rail system in Cincinnati? Cranley says more bike trails, buses will suffice

- Letter: Both political parties have failed us miserably

- Letter: Charge tolls to commercial vehicles at the very least

- Letter: Maybe tea party folks will get us a new bridge

- Letter: Sen. McConnell plays the selfishness game

- Letter: Yet another ugly bridge

- Community reacts to proposed UDF fuel tanker facility

- Streetcar work to cause lane closures

- UDF fuel tanker facility proposed for Norwood

- Geoff Davis: NKY loses with Simpson’s bridge amendment

- Historic restoration topic of weekend workshops

- Mt. Washington residents save greenspace area

- Connector road will join campus with AA highway

- Mallory wants Transit Center to support Banks district

- Part 2: Behind-the-scenes of OTR renovation

- CincyBiz Blog: Cool Places: Get a sneak peek of the Eden Park brewery

- The River City News: Devou Events Center Proceeds, Gus Sheehan Park to Get Facelift

BUILDING CINCINNATI IS FEATURED ON THE FOLLOWING SITES

COPYRIGHT © 2006-2015 BUILDING CINCINNATI. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.